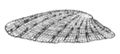

Gastropod shell

1 - umbilicus

2 - Parietal wall of the aperture

3 - aperture

4 - columella

5 - suture

6 - whorl

7 - apex

The gastropod shell is a shell which is part of the body of a gastropod or snail, one kind of mollusk. The gastropod shell is an external skeleton or exoskeleton, which serves not only for muscle attachment, but also for protection from predators and from mechanical damage. In land snails the shell is an essential protection against the sun, and against drying out.

Most gastropod shells are spirally coiled. The coiling is usually right-handed, but in some taxa the coiling is left-handed and in a very few species there can be both right-handed and left-handed individuals.

The gastropod shell has several layers, and is typically made of calcium carbonate precipitated out into an organic matrix known as conchiolin. The shell is secreted by a part of the molluscan body known as the mantle.

Not all gastropods have a shell, but the majority do. In almost every case the shell consists of one piece, and is typically spirally coiled, although some groups, such as the various different families and genera of limpets, have simple cone-shaped shells as adults.

The study of mollusc shells including gastropod shells is called conchology.

Contents |

Chirality in gastropods

Because coiled shells are asymmetrical, they possess a quality called chirality, the "handedness" of an asymmetrical structure.

By far the majority (over 90 %)[1] of gastropod species have dextral (right-handed) shells in their coiling, but a small minority of species and genera are virtually always sinistral (left-handed), and a very few species (for example Amphidromus perversus[2]) show an even mixture of dextral and sinistral individuals.

In species that are almost always dextral, very rarely a sinistral specimen will be produced, and these oddities are avidly sought after by some shell collectors.

If a coiled gastropod shell is held with the spire pointing upwards and the aperture more or less facing the observer, a dextral shell will have the aperture on the right-hand side, and a sinistral shell will have the aperture on the left-hand side.

This chirality of gastropods is often overlooked when photographs of coiled gastropods are "flipped" by a non-expert prior to being used in a publication. This image "flipping" results in a normal dextral gastropod appearing to be a rare and abnormal sinistral one.

The chirality in gastropods appears in early cleavage (spiral cleavage) and the gene NODAL is involved.[3]

Mixed coiling populations

In few cases, both left- and right-handed coiling are found in the same population.[4] Sinistral mutants of normally dextral species and dextral mutants of normally sinistral species are rare but well documented occurrences among land snails in general.[4] Populations or species with normally mixed coiling are much rarer, and, so far as is known, are confined, with one exception, to a few genera of arboreal tropical snails.[4] Besides Amphidromus, the Cuban Liguus vittatus (Swainson), Haitian Liguus virgineus (Linnaeus) (family Orthalicidae), some Hawaiian Partulina and many Hawaiian Achatinella (family Achatinellidae), as well as several species of Pacific Island Partula (family Partulidae), are known to have mixed dextral-sinistral populations.[4] The independent appearance of this variation in unrelated groups is probably the result of a simple mutation, whose primary import is with physiological adaptations to arboreal life and not with the direction of coiling.[4] In Partula both dextral and sinistral embryos have been recovered from the same brood pouch, although normally all embryos coil in the same direction.[4] In Amphidromus there is no information on the heredity of this character.[4]

A possible exception may concern some of the European clausiliids of the subfamily Alopiinae.[4] They are obligatory calciphiles living in isolated colonies on limestone outcrops.[4] Several sets of species differ only in the direction of coiling, but the evidence is inconclusive as to whether left- and right-handed shells live together.[4] Soos (1928, pp. 372–385) summarized previous discussions of the problem and concluded that the right- and left-handed populations were distinct species.[4] Others have stated that these populations were not distinct, and the question is far from settled.[4] The Peruvian clausiliid, Nenia callistoglypta Pilsbry (1949, pp. 216–217), also has been described as being an amphidromine species.[4]

The genetics of reverse coiling in a rare dextral mutant of another clausiliid, Alinda biplicata (Montagu), has been studied by Degner (1952).[4] The mechanism is the same as in Radix peregra (Müller), with the direction of coiling determined by a simple Mendelian recessive.[4] Any change in direction caused by cross-fertilization is delayed one generation by an unknown mechanism.[4]

Formation of the shell

Morphology

Morphology of typical spirally coiled shell. The shell of Zonitoides nitidus, a land snail, has dextral coiling.

Upper image: Dorsal view, showing whorls and apex Central image: Lateral view showing the profile of the shell Lower image: Basal view showing umbilicus in the centre. |

Photo of the shell of Zonitoides nitidus with an apical view, an apertural view and a basal view

|

Gastropod shell morphology is usually quite constant among individuals of a species, and with exceptions, fairly constant among species within each family of gastropoda. Controlling variables are:

- The rate of growth per revolution around the coiling axis. High rates give wide-mouthed forms such as the abalone, low rates give highly coiled forms such as Turritella or some of the Planorbidae.

- The shape of the generating curve, roughly equivalent to the shape of the aperture. It may be round, for instance in the turban shell, elongate as in the cone shell or have an irregular shape with a siphonal canal extension, as in the Murex.

- The rate of translation of the generating curve along the axis of coiling, controlling how high-spired the resulting shell becomes. This may range from zero, a flat planispiral shell, to nearly the diameter of the aperture.

- Irregularities or "sculpturing" such as ribs, spines, knobs, and varices made by the snail regularly changing the shape of the generating curve during the course of growth, for instance in the many species of Murex.

- Ontologic growth changes as the animal reaches adulthood. Good examples are the flaring lip of the adult conch and the inward-coiled lip of the cowry.

Some of these factors can be modeled mathematically and programs exist to generate extremely realistic images. Early work by David Raup on the analog computer also revealed many possible combinations that were never adapted by any actual gastropod.

Some shell shapes are found more often in certain environments, though there are many exceptions. Wave-washed high-energy environments, such as the rocky intertidal zone, are usually inhabited by snails whose shells have a wide aperture, a relatively low surface area, and a high growth rate per revolution. High-spired and highly sculptured forms become more common in quiet water environments. The shell of burrowing forms, such as the olive and Terebra, are smooth, elongated, and lack elaborate sculpture, in order to decrease resistance when moving through sand.

A few gastropods, for instance the Vermetidae, cement the shell to, and grow along, solid surfaces such as rocks, or other shells.

Representation of a shell

Apertural view of shell of Valvata sincera |

Abapertural view of shell of Valvata sincera |

Basal or umbilical view of shell of Valvata sincera |

This dorsal view of the living animal Calliostoma bairdii also shows the dorsal view of its shell |

A shell can be viewed in different ways :

- apertural view : this is the normal representation . The shell is shown in its full length with its aperture to the viewer and the apex on top. When the aperture is on the right side, then the shell is called "right-handed"; if the aperture is on the left side, the shell is called "left-handed".

- abapertural view : the shell is shown in its full length with its aperture 180° away from the viewer and with the apex on top.

- apical view (or dorsal view): the shell is seen in its full width with the apex on top

- basal view (or umbilical view) : the shell is shown in its full width with the apex below. In most cases, the umbilicus is in clear view.

Description

The shell begins with the minute embryonic whorls of the protoconch, which is often quite distinct from the rest of the shell. From the protoconch, which forms the apex of the spire, the coils or whorls of the shell gradually increase in size. Normally the whorls are circular or elliptical in section, but from compression and other causes a variety of forms can result. The spire can be high or low, broad or slender according to the way the coils of the shell are arranged, and the apical angle of the shell varyies accordingly. The whorls sometimes rest loosely upon one another (as in Epitonium scalare). They also can overlap the earlier whorls such that they may be largely or wholly covered by the later ones. When an angulation occurs, the space between it and the suture above it constitutes the area known as the "shoulder" of the shell. The shoulder angle may be simple or keeled, an may sometimes have nodes or spines.

The most primitive sculpture of the gastropod shell consists of revolving ridges or spirals, and of transverse folds or ribs. Primary spirals appear in regular succession on either side of the first primary, which generally becomes the shoulder angle if angulation occurs. Secondary spirals appear by intercalation between the primary ones, and generally are absent in the young shell, except in some highly accelerated types. Tertiary spirals are intercalated between the preceding groups in more specialized species. Ribs are regular transverse foldings of the shell, which generally extend from the suture to suture. They are usually spaced uniformly and crossed by the spirals. In specialized types, when a shoulder angle is formed, they become concentrated as nodes upon this angle, disappearing from the shoulder above and the body below. Spines may replace the nodes in later stages. They form as notches in the margin of the shell and are subsequently abandoned, often remaining open in front. Irregular spines may also arise on various parts of the surface of the shell (see Platyceras). When a row of spines is formed at the edge or outer lip of the shell this sometimes remains behind as a varix as in (Murex) and many of the Ranellidae. Varices may also be formed by simple expansion of the outer lip, and a subsequent resumption of growth from the base of the expansion. These simple varices may project from the shell (Epitonium) or be reflected backwards (Harpa). Periodic enlargements of ribs (Murex, Cerithium) are not to be classed as varices.

The aperture or peristome of the shell may be simple or variously modified. An outer and an inner (columellar) lip are generally recognized. These may be continuous with each other, or may be divided below by an anterior notch. This, in some types (Fusinus, etc.) it is drawn out into an anterior siphonal canal, of greater or lesser length.

An upper or posterior notch is present in certain (chiefly old age) types, and this may result in the formation of a ridge or shelf next to the suture (Clavilithes). An outer (lateral) emargination or notch, sometimes prolonged into a slit occurs in certain types (Pleurotomidae, Pleurotomaridae, Bellerophontidae, etc.), and the progressive closing of this slit may give rise to a definitely marked slit band. In some cases the slit is abandoned and left as a hole (Fissurellidae), or by periodic renewal as a succession of holes (Haliotis). The outer emargination is often only indicated by the reflected course of the lines of growth on the shell.

On the inside of the outer lip, various ridges or plications called lira are sometimes found, and these occasionally may be strong and tooth-like (Nerinea). Similar ridges or columellar plicce or folds are more often found on the inner lip, next to the columella or central spiral twist. These may be oblique or normal to the axis of coiling (horizontal), few or numerous, readily seen, or far within the shell so as to be invisible except in broken shells. When the axis of coiling is hollow (perforate spire] the opening at the base constitutes the umbilicus. The umbilicus varies greatly in size, and may be wholly or in part covered by an expansion or callus of the inner lip (Natica).

Most modern shells are covered by a horny smooth or hairy epidermis or periostracum, which sometimes hides the (often brilliant) color markings of the surface. The periostracum, as well as the coloration, is rarely preserved in fossil shells.

The apertural end of the gastropod shell is the anterior end, the apex of the spire the posterior. Most authors figure the shells with the apex of the spire uppermost. French authors generally figure them with the anterior end uppermost. The aperture is often closed by a horny or calcareous operculum, of very variable form in the different groups. It is secreted by and attached to the upper surface of the foot of the animal.[5]

Parts of the shell

The terminology used to describe the shells of gastropods includes:

- Aperture: the opening of the shell

- Apex: the smallest few whorls of the shell

- Body whorl: the largest whorl in which the main part of the viseral mass of the mollusk is found

- Columella: the "little column" at the axis of revolution of the shell

- Operculum: the "trapdoor" of the shell

- Parietal callus: a ridge on the inner lip of the aperture in certain gastropods

- Periostracum: a thin layer of organic "skin" which forms the outer layer of the shell of many species

- Peristome: the part of the shell that is right around the aperture

- Protoconch: the larval shell, often remains in position even on an adult shell

- Sculpture: ornamentation on the outer surface of a shell

- Lira: one kind of shell sculpture

- Plait: another kind of shell sculpture

- Siphonal canal: an extension of the aperture in certain gastropods

- Spire: the part of the shell that protrudes above the body whorl

- Suture: The junction between whorls of most gastropods

- Umbilicus: in shells where the whorls move apart as they grow, on the underside of the shell there is a deep depression reaching up towards the spire; this is the umbilicus

- Varix: on some mollusk shells, spaced raised and thickened vertical ribs mark the end of a period of rapid growth; these are varices

- Whorl: each one of the complete rotations of the shell spiral

Shape of the shell

The distinction of the shape of the shell may vary based on the purpose. For example distinguishing into three groups can be based on the height - width ratio:[6]

- oblong - the height is much bigger than the width

- globose or conical shell - the height and the width of the shell are approximatelly the same

- depressed - the width is much bigger than the height

|

oblong shell of Bulgarica denticulata |

globose shell of Sphincterochila candidissima |

depressed shell of Escargot de Quimper |

Detailed distinction of the shape can be:[7][8]

cap shape |

ear shape |

neritiform |

planispiral |

depressed trochiform or valvatiform |

trochiform |

ovate-conic |

conic |

|

elongate-conic or turriform or cockscrew shape |

top shape |

spindle shape - the sea snail Syrinx aruanus has the largest shell of any living gastropod. |

club shape |

barrel shape |

egg shape |

irregular shape |

Pear shape means both shapes: ovate-conic and conic.

Dimensions

The most frequently used measurements of a gastropod shell are: the height of the shell, the width of the shell, the height of the aperture and the width of the aperture. The number of whorls is also often used.

In this context, the height ( or the length) of a shell is its maximum measurement along the central axis. The width (or breadth, or diameter) is the maximum measurement of the shell at right angles to the central axis. Both terms are only related to the description of the shell and not to the orientation of the shell on the living animal.

The largest height of any shell is found in the marine snail species Syrinx aruanus, which can be up to 91 cm.[9]

The central axis is an imaginary axis along the length of a shell, around which, in a coiled shell, the whorls spiral. The central axis passes through the columella, the central pillar of the shell.

Evolutionary changes

Among proposed roles invoked the variability of shells during evolution include mechanical stability,[10] defence against predators,[11] sexual selection[12] and climatic selection.[13][14]

The shell of some gastropods have been reduced or partly reduced during the evolution. This reduction can be seen in all slugs, in semi-slugs and in various other marine and non-marine gastropods. Sometimes the reduction of the shell is associated with predatory way of feeding.

Some taxa even lost the coiling of their shell during evolution.[15] According to Dollo's law, it is not possible to regain the coiling of the shell after it is lost. Despite that, there are few genera in the family Calyptraeidae that changed their developmental timing (heterochrony) and gained back (re-evolution) a coiled shell from the previous condition of an uncoiled limpet-like shell.[15]

Variety of forms

|

Turritella communis, many-whorled shell of tower snail |

X-ray image of Turritella |

Shell of marine cowry snail - Cypraea nebrites |

X-ray image of Cypraea |

X-ray image of the shell of Tonna galea |

Charonia |

Murex pecten |

Thin section in plane-polarized light of microscopic gastropod shell, from Holocene lagoonal sediment of Rice Bay, San Salvador Island, Bahamas. Scale bar 500 microns. |

References

This article incorporates public domain text from references [4][5] and CC-BY-2.0 text from reference [14] .

- ↑ Schilthuizen M. & Davison A. (2005). "The convoluted evolution of snail chirality". Naturwissenschaften 92(11): 504–515. doi:10.1007/s00114-005-0045-2.

- ↑ Amphidromus perversus (Linnaeus, 1758)

- ↑ Myers P. Z. (13 April 2009) "Snails have nodal!". The Panda's Thumb, accessed 3 May 2009.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16

Laidlaw F. F. & Solem A. (1961). "The land snail genus Amphidromus: a synoptic catalogue". Fieldiana Zoology 41(4): 505-720.

Laidlaw F. F. & Solem A. (1961). "The land snail genus Amphidromus: a synoptic catalogue". Fieldiana Zoology 41(4): 505-720. - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Grabau A. W. & Shimer H. W. (1909) North American Index Fossils Invertebrates. Volume I.. A. G. Seiler & Company, New York. pages page 582-584.

- ↑ Falkner G., Obrdlík P., Castella E. & Speight M. C. D. (2001). Shelled Gastropoda of Western Europe. München: Friedrich-Held-Gesellschaft, 267 pp.

- ↑ Hershler R. & Ponder W. F.(1998). "A Review of Morphological Characters of Hydrobioid Snails". Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 600: 1-55. [1].

- ↑ Dance P. S. (). Shells.

- ↑ Wells F. E., Walker D. I. & Jones D. S. (eds.) (2003) "Food of giants – field observations on the diet of Syrinx aruanus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Turbinellidae) the largest living gastropod". The Marine Flora and Fauna of Dampier, Western Australia. Western Australian Museum, Perth.

- ↑ Britton J. C (1995) "The relationship between position on shore and shell ornamentation in 2 size-dependent morphotypes of Littorina striata, with an estimate of evaporative water-loss in these morphotypes and in Melarhaphe neritoides". Hydrobiologia 309: 129-142. abstract.

- ↑ Wilson A. B., Glaubrecht M. & Meyer A. (March 2004) "Ancient lakes as evolutionary reservoirs: evidence from the thalassoid gastropods of Lake Tanganyika". Proceeings of Royal Society London Series B - Biological Sciences 271: 529-536. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2624.

- ↑ Schilthuizen M. (5 June 2003) "Sexual selection on land snail shell ornamentation: a hypothesis that may explain shell diversity". BMC Evolutionary Biology 3: 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-3-13.

- ↑ Goodfriend G. A. (1986) "Variation in land-snail shell form and size and its causes – a Review". Systematic Zoology 35: 204-223.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Pfenninger M., Hrabáková M., Steinke D. & Dèpraz A. (4 November 2005) "Why do snails have hairs? A Bayesian inference of character evolution". BMC Evolutionary Biology 5: 59. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-5-59

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Collin R. & Cipriani R. (22 December 2003) "Dollo’s law and the re-evolution of shell coiling". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 270(1533): 2551-2555. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2517.

Further reading

| Seashell topics |

|

| About mollusc shells |

|---|

|

Clam shells |

|

Conchology |

| About other seashells |

|

Brachiopod shells |

- about chirality

- van Batenburg1 F. H. D. & Gittenberger E. (1996). "Ease of fixation of a change in coiling: computer experiments on chirality in snails". Heredity 76: 278-286. doi:10.1038/hdy.1996.41.

- Wandelt J. & Nagy L. M. (24 August 2004) "Left-Right Asymmetry: More Than One Way to Coil a Shell". Current Biology 14(16): R654-R656. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.010

External links

- Gastropods by J. H. Leal - Information on some gastropods of the tropical Western Atlantic, specifically the Caribbean Sea, with relevance to the fisheries in that region

- Radiocarbon Dating of Gastropod Shells

- Nair K. K. & Muthe P. T. (18 November 1961) "Effect of Ribonuclease on Shell Regeneration in Ariophanta sp.". Nature 192: 674-675. doi:10.1038/192674b0.

- (Spanish) Antonio Ruiz Ruiz, Ángel Cárcaba Pozo, Ana I. Porras Crevillen & José R. Arrébola Burgos Caracoles Terrestres de Andalúcia. Guía y manual de identificación. 303 pp., ISBN 84-935194-2-1. (from website)